BROWSE Columns

✕

Soft and mournful, that’s how it begins.

And where it begins is where I have to go, but I’m not ready yet. I’m still waiting for the last dose of morphine to seep into my broken bones and out to my raw scraped skin. I need to concentrate and I can’t when my mind is dragged towards the pain like a compass point to north. Perhaps it’s a cruel trick to play on myself, putting so much weight on what I’m about to try. I’m only trying to remember a song. But, no, it’s more than that. I’m trying to remember me.

Low notes, heavy with gravity—a basssline or a guitar?

I was screaming when I woke up in the hospital but I think I stopped when I realised I couldn’t hear myself. A nurse rushed to calm me and scribbled a note to tell me where I was and that I was okay. I already knew that was a lie. I think he put something into my IV because I was soon swallowed again by sleep in one deep gulp. When I next woke, handwritten notes were already prepared and a doctor held them up so I could read. I was in the Royal Infirmary Hospital in Newcastle. I’d been in an accident and emerged with 15 broken bones, a punctured lung, a fractured skull, and two perforated eardrums. My hearing might come back, but it might not. I half-expected one note to say I was lucky to be alive. Nobody was that unwise.

The sound of a song as a soul.

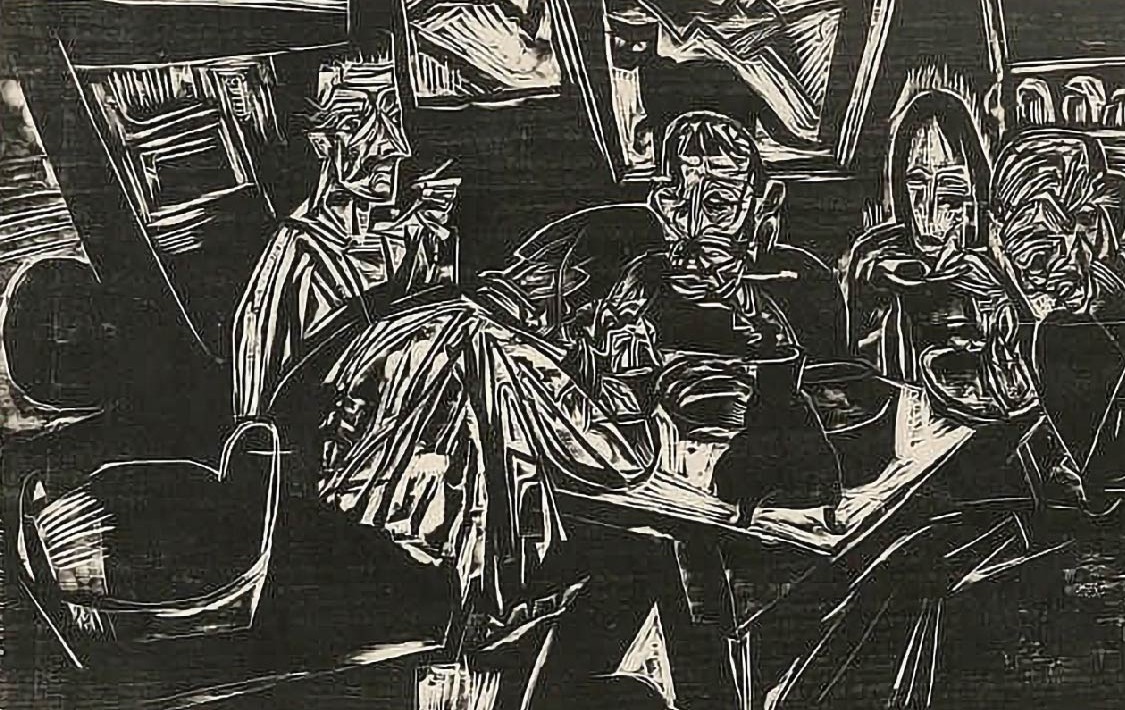

I’ve been drifting in and out of sleep and moods, as the drugs in my blood ebb and flow. Sometimes my thoughts have been dull, thick and soft as rainclouds, sometimes they sharpened into lightning bolts. But they always circle back to variations on the same question, one I’ve never asked myself before. Who am I? A simple question, but it breaks into two when I probe it. Who was I before? Who am I now? What I’ve worked out is this: most of what I call me is a patchwork quilt made of other people. My soul is fragments of other souls—people I know or have known, or people I felt like I knew through the things they wrote or the songs they sang. Perhaps I never asked myself who I was because the answer always seemed obvious to me—I was right there in the music I have always loved. The only guides I’ve ever had in life were singers. Joni Mitchell has been by my side since I was twelve, when my mother decided I was old enough to graduate from Ziggy Stardust’s dazzle and Parade’s strut and move into the subtleties of Blue. Joni is who I’m going to seek now, the only way I can—through a song. Through Amelia, the song Ben and I were listening to that night.

There is a hexagram in the heavens.

Music is the only magic I’ve ever believed in—this mystical act of translating emotions too subtle and complex for words into the more mysterious and expansive language of music. Turning a song into a recording resembles magic, but can be scientifically explained. It goes like this: in the month I was born, a Canadian singer-songwriter called Joni Mitchell sat in a low-lit studio in Hollywood and played and sang a new song she’d written. A song inspired by lost love and the melancholy tug of wanderlust. The sound of the song was codified into an electric signal which was then arranged into magnetic particles on the surface of a spooling tape. That’s all. That’s everything.

You have to get there yourself.

The morphine’s beginning to work. I can feel it defanging my pain, allowing me to calm and concentrate. Medicine is another science that feels like magic. Like studio tape transfigured into black vinyl, then copied and shipped across the world, or transformed into strings of 1s and 0s to be recreated as sound instantly and anywhere. With the pain fading, I am ready now, ready to search for a song.

Songs scramble time and seasons.

What science can’t explain away is that final miracle, that communion between song and listener, that transubstantiation of sound into emotional truth. How is it possible that sounds can vibrate through the air and our spirits will soar, swoon or shiver in response? How can it matter so much to us that we’ll try to hold onto these moments in our memories? That’s where I’m going now, into my memories. I hope I’ve held onto enough of Amelia. If my hearing is gone forever, memories are all I’ll have left of it—and all the other songs I’ve loved so hard and for so long that I don’t know who I’d be without them. I can’t lose music, not on top of all else. I close my eyes and lie very still in this hard bed and send my mind inside myself, looking for a song that’s threaded through two thirds of my life. For a bleak empty moment there is absence and then…

Mournful, shimmering notes, stumbling over each other in the first steps before flight.

The relief I feel is as powerful as that delivered by the painkillers, and much more profound. I can hear the song in some strange way, somewhere deeper inside me than my eardrums. A place that some might call a soul. The first notes of Amelia are plangent, vibrating guitar. Of course. Not a bass—that comes later. But when does Joni begin to sing? I don’t remember, not exactly. Panic flutters in my chest, but I keep it caged. That doesn’t matter right now. First, I need to find her words. After a long frightening moment of nothing, I remember. Joni starts by telling us of how she was driving across a desert and witnessed the vapour trail of disappeared jet planes crisscrossing the sky. And now—just like that—I am with her, and we are driving together across barren American landscapes, and she is singing.

A voice delicate but strong, like wings ascending.

She sings of flying and driving, and how it feels to be alive and alone on our long, strange journeys from our cribs to our coffins. For the first time since the accident, I feel something like happiness. Though I remember Amelia imperfectly, I’ve kept enough for it to live on inside me. If I believed in a God, I’d thank him for every time I listened to this song, every time I sat on a train or plane and lost myself inside its roaming reveries, every time I played it to someone new and told them to close their eyes and watched their face for any sign that the magic was working on them too. Because every time I did, I transferred more of the song to my memory, like a voice to tape.

Joni’s voice dips and climbs, dips and climbs, as if riding air currents.

When did I first play Amelia to Ben? The details are smudged, but I think it was in our early days, that wild tumble of new love and hedonism. When golden eagles are seeking a mate, they plummet through the sky like acrobats. We were eagles back then, daring each other on. That night we were in my bedsit at 4am and drinking lager to blunt the chemical comedowns we’d earnt in the club earlier. I must have played Amelia to impress him or seduce him. With the distance of eighteen years and all my knowledge of Ben since, I realise now it must have bored him that first time. Six minutes of drifting, form-free mood, no real chorus to focus on, not even a drumbeat as anchor—what was I thinking? But Ben being Ben, he was too sensitive to say it dragged on and later he really would learn to love Amelia. Almost as much as me.

Metaphor upon metaphor: we are Joni, Joni is Amelia, Amelia is Icarus and together we soar and together we fall.

The lovestruck eagles pull out of their falls, one terrifying instant before they crash. Ben and I weren’t so lucky. The doctors say he died instantly. I’m glad of that mercy. He had no time for fear, no realisation that the song that was him was about to end right in the middle of its melody. The last thing I can remember from that night is the sighing space between the fourth and fifth verse of Amelia. I don’t remember the accident, not the sheep Ben swerved to avoid on a rainy Northumbrian road, or the truck we smashed into with a force terrible enough to shatter his skull instantly and loud enough to shred my eardrums. I was lying in the back seat, eyes closed, half-dozing and half-listening. Then I was here, in the hospital.

No dramatic climax: the song fades out, and in its slow waning there is something cyclical, as if the song will inevitably wax and return to where it began and play again.

I open my eyes. My world’s still broken but I have salvaged something from the wreck. I now know there are other songs I’ll be able to retrieve. For today, Amelia is enough. Perhaps tomorrow I’ll search for Sound and Vision or Mayonaise, another of those songs that sit deep in the foundations of my being. I know that as long as I hold onto them, I’ll still be me, even in that shadowy and uncertain place that is now my future. I will live. I won’t have Ben by my side, won’t be able to squeeze his arm to be sure of him, but I will have pieces of him, captured in songs and memories and fragments. That’s all there ever is, when our long, strange journeys end—memories and fragments, the souvenirs we pocketed along the way.