BROWSE Columns

✕

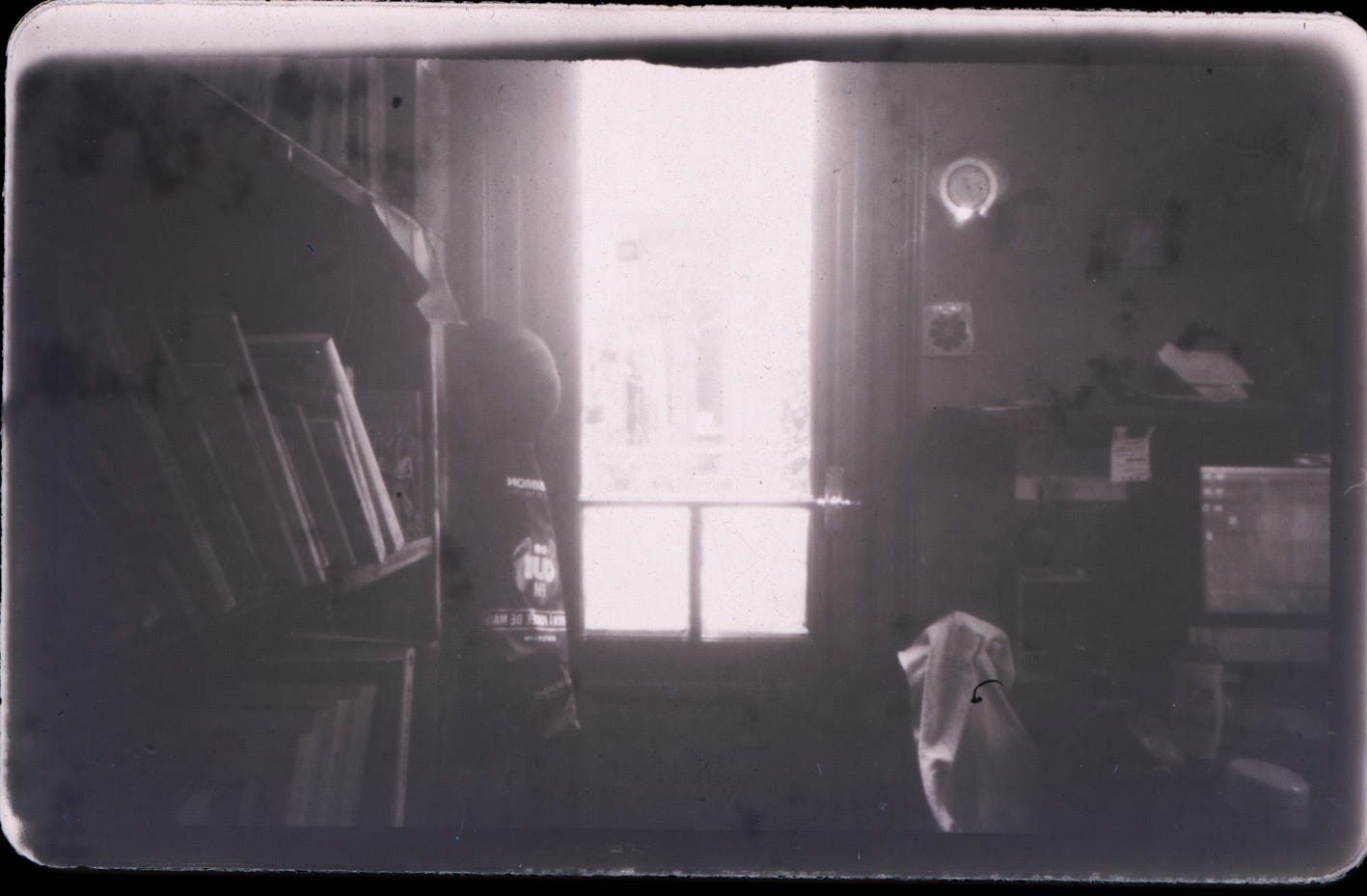

This interview with the artist Vareila Mairanga concerns a series of 3 photographs, entitled “Las últimas 8.” The project is a documentation of the final 8 hours in a house she lived in and was about to leave. The exposure of each of these photographs lasted 8 hours (captured on handmade pinhole cameras). People entered and exited the frame, furniture was removed, and what remains is the space itself. The human presence does not appear, and ultimately represents only a fleeting moment here.

Micaela Brinsley: What was the initial inspiration for putting together this project?

Vareila Mairanga: This series was shot in 2016 while I was starting to study analog photography and I had started practicing pinhole photography not far before. I was quite astonished by the time of exposure that pinhole photography offers and requires. I wanted to take some pictures of the house I was living in because it was my first house in Buenos Aires where I had porteños, porteñas roommates. The two houses, three houses before that, were only filled with foreigners. This was my first experience of living in a porteña house, and also it was a house where I felt really well and where I had friends and it felt like home. Suddenly the landlord, the dueño, decided to take it back. The girls who were living there had been living in that house for 12 years. They were in their 30s and I think that they arrived in that house when they were 20. They just rented a very big house for five of them and just started living there. There were so many people that lived in that house—the rolling of people was such that when they did the goodbye party for the house, I had the feeling that all Buenos Aires was there. It was not the case, but you know what I mean. It was crazy how many people knew this house and knew about it.

I really wanted to keep something from that house. I didn't have anything I could do to manage my feelings—there's nothing you can do about what's happening and you just have to bear what you're feeling. What you're feeling is weird and you don't know what to do about your feelings. Most of the time when I feel like that, I just take the camera and start doing stuff without even realizing [what] I'm doing. I decided that I wanted to practice a little bit of pinhole in the house.

This was my first time photographing pinhole indoors. When I measured the light, it indicated eight hours. I was like, what? That's not possible—I cannot shoot this for 8 hours, we have to leave the house in 10. Then I just decided why not, if it's gonna work, this could be really interesting. I knew how the printing of the image worked, it was something I really understood in terms of its theory. Suddenly, I could do something to see it in practice. I thought, that's gonna be really interesting because these are gonna be my last hours in the house and it's gonna be printed.

At the time, I was reading about the fact that there are 3 kind of images—there is what we call the image indicial because there is a physical link between what was in the reality and what ends up in the image. I was just thinking that those last eight hours of the house are physically gonna be printed on that image. That's beautiful. The people who went through the image and the furniture left the room are also going to be somehow physically present on the paper. I really like the interpretation of the concept of imagen huella, that those images could give me.

Imagen huella is an indexical sign—an image that results from direct contact or physical connection with its referent, rather than from resemblance (i.e. icon) or symbolic meaning (i.e. symbol). This is a notion derived from Charles Sanders Peirce, the father of semiotics. The word directly translates to “image trace,” but in English I feel as if part of the meaning is lost. But in essence, it refers to an image that maintains a physical or casual connection with the object it represents (in this case, light).

I wasn’t sure it was going to work.

I only had one shot.

I put different cameras in different rooms, but I only had one shot and I didn't have my dark room in that house. Somehow, I was going to take those pictures and either it works, or it doesn't. It did. I was quite surprised. That's the moment where I really understood the power of pinhole photography—the part of the world that it can show me, the way it proposes a new eye on the world, something my eyes could never see. I think that was the exact moment where I understood the power of pinhole photography—and I fell in love with it.

What are some of your artistic inspirations and how do you integrate their influence (or not) into your work?

I was actually trying to think about inspiration. I'm the kind of photographer that is not so fond of photography. There are so little things in photography that I actually like. I like Maya Deren's work, it's more cinematography—it's the photographic aspect of her movies that I like. But then I just couldn't think about anyone else or specific things I have seen in festivals. But I wouldn't say they’re actually an inspiration.

You had me thinking on that question for a while, because yesterday when I wanted to answer it, I was like… but who else except Alix Cléo Roubaud? If I have to think so hard about who I would talk about as an inspiration, it means there were not [that many] I guess, or if there were, it was more in an unconscious way. Something was there and my mind kind of grabbed onto it. But it wasn’t a real “inspiration.”

In terms of Alix Cléo Roubaud, I discovered her work not long before I started school [in Buenos Aires] in 2014 or 2013. I went to an exhibition in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the National French Library. It was close to the university where I was going. I think I saw an image and I asked myself, who is she? So I went and saw her work. I don't know if I was that much into photography at the time. I had a digital camera and I really liked shooting. But it was a very, very different experience of photography. I was not the same photographer as I am now.

When I saw her work, I couldn't point out exactly what, but I really felt something. It was really, really strong and deep. I just fell in love with her work.

A few years after, maybe 2015 or 2014, I bought a book—it was a biography about her, but the author took a little bit of freedom in the way she was writing it. It was so, so interesting. Something important about the work of Alix Cléo Roubaud is that she doesn't consider the photographic image created when you're shooting the image, but that it is created in the darkroom.

She would work with negatives that were not shot by her—because she would consider that her being the person making the copy in the darkroom and manipulating the image in the darkroom (which is the image that the spectator will see) is the moment where you create the photography. It doesn't matter who shot the image. It matters who made the printing.

She had so many different ways of working in her darkroom, it was so interesting. She even invented (well, I don't know if she invented it, I'm not sure), but she used a tool that is called in French, le pinceau lumineux, which means the lighting brush. It was like using a painter's brush, but instead of having paint, you would have light. She made very beautiful things.

Reading her book, I was just not believing what I was reading. It was so inspiring. I’d never noticed how aesthetically close to her work my work is. It took me a very long time to see that. I never tried to copy her, I never tried to get close to her aesthetic. I guess she was present in my mind and it's an aesthetic that I like, so I guess I went toward that. I didn't intentionally get close to her aesthetic, but I always had in mind the idea that the subject and what you shoot is not always the main part of the creation of your image.

What was the process for the photography that you came up with before the shooting, and how did the actual recording challenge (or not) the plan you had in mind?

I have the feeling that I partly answered it in my first response, but I really wanted to photograph that first place in Buenos Aires where I felt at home. The challenges were that I was experimenting in one of my first times trying to shoot a pinhole in interiors.

I was challenged by the lack of light—before, I hadn't thought about it so much. I didn't have in mind how powerful sunlight is, how much you have to divide the light, the quantity of light as soon as you get inside of walls. Somewhere where you have walls is not filled with sunlight—I didn't have that in mind at all.

When I calculated the exposure time, I was surprised by the eight hours. I think that also gave me a chance to understand the power of light and realize how much our eyes adapt all the time by closing and opening the pupil, the equivalent of the diaphragm in the camera. It also makes sense when you think about that—the camera is an exact copy of our eye. Our eyes work the exact same way a camera works. The camera was inspired by our eyes.

In any event, I think that moment I described was incredible because I got to really understand it. Not only in a theoretical way—if you give me the science of it, I understand it. But I think that at that moment, I was able to actually comprehend it.

I think those were the challenges that I encountered, the sense that I have no idea if it's going to work.

But also I have the feeling that it's a big, big part of my work—I usually don't really know what I'm going to have as a result. And somehow, I don't really care. First of all, because the process is so interesting—it is a whole part of the image. I love so much how surprised I can be, when I am not expecting anything. I think that's why I don't really care. This experience was the first time getting into that relation with creating my images, understanding the fact that I don't know what I'm going to obtain. And that it’s not an issue for me—it’s more interesting than anything else.

How did the development of the photographs surprise you?

I guess I was surprised that it was so well exposed. A very stupid surprise was to know that I can trust my phone's photometer, because I was very, very suspicious about that. Like an app? I can measure light with an app? I don't think that could, and it did. It actually did very well. I’ve explained to you before that photography is always negative—because usually silver nitrate oxidates with the contact of light. So, the more light a photosensitive surface receives, the darker it gets. The less light it receives, the lighter it stays. So, it's always going to be negative. When I developed the images, I had negatives. At that time, I was not yet experienced enough to know if I had a good negative or not. So, I didn't really know what I was seeing. I didn't really know if it was a good image. When I saw it with my little app that sees negatives... I was surprised that it was that good and that I had that level of detail.

The second surprise came when I scanned them and realized that the part where I wanted to have some furniture present, worked. I was expecting people to be more printed. But then I understood the science behind that—it's because the ratio between the time of exposure and the time people would stay in frame was too unbalanced for it to work.

What are you currently working on at the moment?

I'm photographing people who have scars they love and wouldn't get rid of for anything in the world. They consider those scars part of who they are today. The challenging part of this work is that I wanted it to be pinhole photography. I also work on X-ray paper, which, so far, is not so complicated. The complicated parts come when I want to make direct positives.

The same way I mentioned that photography is always negative, I want the spectator to look at the same image that I've captured. I don't want to make a positive (copy) of the image that I captured—I want it to be the image that the spectator will see.

I'm definitely convinced we had this conversation because I remember that you asked why the positive is always the final destination of a photographic image and why we couldn't consider the negative as its final form. Now that I'm remembering that, I’m going to think a little bit more about it. At the time you told me that, I wrote it in my notebook, hey, this is something to think about, but I guess I forgot about it. Photography-wise, I'm not working on any other specific project other than that, because it has been a tough year.

When you look at them now, do they make you think of home? Or ghosts, perhaps ones containing your memories that linger in your old home?

I hadn’t looked at this series for the longest time—except a few months ago, I had to make a portfolio for an application and I was trying to find a red line through my work. I remembered this work and thought to myself, you're not so far from that, you really like that kind of thing. You kept on working this way, even though you didn't think about it. I started looking at them again. I never applied to anything with these images, because they were my first interesting images, but I never thought they were interesting enough. When I looked at them a few months ago for the first time in I don't know how many years—I liked them.

I don't think looking at them reminded me of home. But the fact that they exist, the fact that I made this series, has always been present in my mind. It always brings me back to the idea that that place felt like home. It's not the images themselves that give me that feeling, but the fact that I made them. So, even though I didn't look at them for years, I never forgot they existed. I always had this reminder of the act, the geste, I would say in French, that I did it. It was home and I was very sad. I remember, I was very sad, and somehow it was my only way to deal with what I was feeling. I came to realize that I often do that. But I don’t think this by looking at them—it's more knowing that I did them.

They don't remind me of ghosts, but they do have, now that I'm reading the question again, there is something that lingers. I'm talking about the image itself, I hope I'm making sense. The images themselves contain, maybe not memories that linger, maybe not my memories… but I do have the feeling that I captured the memories of a house that was everyone's house.

When I look at them, I have this feeling that these walls are printed in these images, and all the people that stayed in between these walls are in this image, now.

Vareila Mairanga (Kenya, 1990) is a Franco-Kenyan director, cinematographer and photographer. Based in Paris, she lived and worked in Buenos Aires for over 10 years, where she graduated from the ENERC university in DOP and completed the Programa de Cine at the Di Tella University. Her practice focuses on the tactile and archival dimensions of the image. She explores the intersection of materiality and narrative through experimental approaches such as laboratory support manipulation, device construction and/or modification. Her work engages with images that evoke both the haptic and the archival, where the medium exists simultaneously within and beyond an elusive yet tangible discourse. Vareila’s work has been exhibited, among others, at FIDBA (Argentina), Jinny Street Gallery (Japan), Revela'T (Spain), the Argentinean Biennial of Documentary Photography, LALIFF (USA), FFIMBB (Argentina).