The (Un)State of Heidi’s Eyebrows

Relieved of her eyebrows, Heidi feels a renewed sense of purpose, a development so affronting from the eyebrows’ perspective they feel compelled to leave Heidi a note.

Even among contemporaries as heterogeneous as writers, Heidi has always stood out, less for her appearance (which is signally ordinary, even with her eyebrows, which are themselves uneventful as far as eyebrows go), more for her efficiency and unwavering certitude. Heidi writes to the clock, starting at 8:45 each morning, breaking for tea at 10, made always in the same pot at 84 degrees and steeped for 15 seconds. On walks, Heidi powers under ladders, coddles black cats; cracks in the footpath never dissuade her lest she egregiously deviate from her set path.

Heidi’s body moves in accordance with her mind, a perpetual motion machine in which every atom plays a functional and purposeful role. Not surprising in the least, then, that Heidi studies herself in the mirror one night (is that grey showing in her neat auburn bob? her skin … she’s beginning to get crinkles around her eyes; not to mention her eyebrows … eyebrows …) and can’t help but wonder what exactly her eyebrows are for.

There are obvious examples of the value of a nose both literally and figuratively. Besides its physiological purpose, a person can be ‘nosey’ or (who knows) ‘on the nose’, similarly a big mouth is best advised to keep their lips sealed. Heidi googles: ‘sayings with eyebrows in them’ and learns eyebrows’ neighbour the ‘brow’ could be ‘high browed’ or ‘brow beaten’ (poor brows, thinks Heidi, furrowing her brow). But of the eyebrows themselves? Nothing. They really serve no purpose.

So Heidi takes her razor and she shaves them off.

At first Heidi feels liberated, indeed her life would have continued in its unremitting upward trajectory, had her eyebrows not so persuasively stated their case in the note they leave on Heidi’s desk:

Dear Heidi

From exile in your shoe cupboard, we write to express our profound disappointment at your recent dislodgement decision. We note grave due process violations related to our case: you provided neither prior notice for your decision; nor legal recourse to challenge it.

Dispossessed of our home and deprived of our most basic rights, we consider your act arbitrary, wrong and woefully short of personal grooming best practice.

Also, the shoe cupboard is dank and cramped. We have nothing but two minute noodles, fluff and old cat biscuits to eat.

We urge you to take effective steps to rectify the situation.

Yours sincerely,

Your eyebrows

Heidi places the note back on her writing desk. Pugnacious; lumpish; lacking specificity: precisely the qualities that have always troubled Heidi about her eyebrows. Heidi doesn’t regret her decision at all. This is, at least, her initial reaction.

Everything begins to change, though, when Heidi sits down to dinner. At precisely 7pm, Heidi sets her place at her home-carpentered dinner table. She goes to pour herself a glass of wine, returns, and sits down. Realising just how hungry she is, how welcome these few minutes to recharge and contemplate, Heidi reaches for her knife and fork. She leans forward, her tummy rumbling in eager anticipation (how long has it been since she last ate?) … and pauses. There stand her two meat pies, crowned by her eyebrows, staring up at her from the 70s-style ceramic dinnerplate. Heidi flinches, stands back up, and wastes no time in chucking the whole lot in the bin.

Sometime during the night Heidi gets up to go to the bathroom. Bleary-eyed, she fumbles with the light switch, pulls on her dressing gown, and stumbles across the cold tile floor. Wishing she hadn’t had that cup of tea right before bed, she reaches out to lift the toilet lid … and pauses. Rubbing her eyes – this time in disbelief – she observes her eyebrows who have planted themselves astride the toilet lid and are staring at her with their blind eyes. ‘What a vexatious situation … what to do now?’ Heidi wonders. Heidi climbs back into bed and holds it ‘til the morning. Then she goes outside and pees on the lemon tree.

At 8:45am, having downed two cups of coffee over her usual tea, Heidi sits down at her computer to begin work, determined to put the previous night’s events behind her. She troubles the mouse, and her screensaver clears. There, staring back at her, is a desktop image of her own eyebrows. They float across the screen painting a hypnotic AI artwork in cyan and magenta. Is it a secret code, a snarky message written in eyebrow? Heidi is riled. It takes 10 minutes to pull the plug and re-set.

Clearly, Heidi needs to reconsider the eyebrows’ case – for practical reasons alone: whilst her eyebrows failed to make a meaningful contribution on her face; they’re wreaking havoc in her life now they’ve been dislodged, not mention the niggling nostalgia she’s starting to feel for the two sleepy sables that once lolled listlessly over her eyes. Reconsidering the note carefully, Heidi concedes their case for statelessness and procedural unfairness is compelling. Perhaps she’d been a bit rash, if not a tad mean.

So Heidi invites the eyebrows to a mediation, which she asks her neighbour Archibald to facilitate.

Archibald works at Border Force, and she feels confident he knows the ins and outs of international law. They meet in Archibald’s starkly furnished home office, Archibald sitting across the desk from Heidi and her eyebrows, a stack of forms and papers between them. Heidi glances at the letterhead and notes Archibald’s mission is to protect Australia’s borders and treat alI people with respect, dignity and fairness. Isn’t that a contradiction? wonders Heidi, recalling images of desperate people jumping off the sides of barely seaworthy boats and into the ocean.

Heidi pulls out the note and begins: ‘I wasn’t quite sure how to resolve this Archibald, I was hoping …’

‘If it doesn’t feel right, flag it. Archibald takes the note and studies it. ‘What’s your nationality? (Archibald addresses the eyebrows directly).

‘Sorry?’ The eyebrows feel cowed.

‘Your nationality. In which country are you legally a citizen?’ The eyebrows don’t hold any citizenship. They are not a national of any country. They are eyebrows, after all.

‘Non-Australian citizens resident in Australia without a visa are deemed unlawful non-citizens and must be detained under the Migration Act 1958. You’ll need a visa if you wish to stay.’ Heidi observes Archibald’s stamp. It’s a very big stamp, of which Archibald is immensely proud. Heidi asks Archibald what he would suggest.

‘Might I suggest you try a protection visa subclass 866, global special humanitarian visa subclass 202, or a refugee visa 200, 201 or 204?’ says Archibald. The eyebrows stare at Archibald. They’re unsure what subclass numbers contribute to this conversation.

‘How long would that take?’ Heidi asks.

Archibald admits the decision process could take many months, even years, which Heidi acknowledges is a very wide timeframe and asks Archibald to be a bit more specific, at which point Archibald twiddles his big stamp and surmises an average of seven years, give or take.

Heidi wonders what the prospect of a refugee visa actually being approved is (a critical question given the precariousness of the eyebrows’ situation), to which Archibald quickly responds that the number of applications is always far greater than available visas. Heidi refrains at this point from requesting greater specificity. She rates success as unlikely to impossible.

‘How about a family visa then, given our deep personal connection?’

Archibald nods slowly, shuffles his papers and looks at the eyebrows: ‘can you please tell me Heidi’s favourite colour, movie and dish?’

‘Excuse me?’ (the eyebrows, patently confused).

‘I need you to tell me Heidi’s favourite colour, movie and dish. It demonstrates the legitimacy of your relationship.’

The eyebrows have an intimate understanding of Heidi’s life and of the inner workings of her soul. They’ve felt every moment of joy, pleasure and pain since Heidi was born. But her favourite colour? Applied to what – living room interior, eyeshadow, pool noodle? Who has a favourite colour beyond the age of five? The eyebrows are perplexed. They haven’t a clue.

Heidi interjects. ‘Wouldn’t our ability to answer those questions just underscore how trivial our relationship is? I mean, if this was a scam, aren’t those exactly the things we would be able to answer because we’d have rehearsed them exhaustively? Surely a relationship significant enough for someone to uproot their life, work and friendships must be founded on something more … solid?’

Archibald looks at Heidi blankly.

‘Blue. Gone With the Wind. Sausages.’ The eyebrows blatantly make it up.

Archibald nods approvingly at these choices. He scribbles some notes on his papers, raises his very big stamp and slams it down, emphatically, like he’s been waiting for this moment his entire life.

‘Your paperwork seems to be in order.’ Archibald is content.

The eyebrows breathe a sigh of relief.

‘I’ll just need the application fee of $9,095.’

Despite the obvious ethical concern that a family’s right to remain united should not hinge on the faculty of a large bank account, the eyebrows do not possess $9,095.

Their application is denied.

Heidi is mortified. She honestly had no idea the system would be so unfair. Perhaps resettlement would be an option? She discusses this idea with Archibald, who suggests the Gaugin at his uncle Terence’s house.

Heidi has only been to Terence’s once, but she remembers the feeling of being transported to another dimension where dirt doesn’t exist, light and air hang in equal proportions in tranquil inside-outside interiors, and infinity pools defy gravity by merging seamlessly with the Brisbane River. Transcendence, Heidi thinks, effortlessly procured with mining money.

Heidi recalls the Gaugin hung artfully on Terence’s living room wall. Yes, it would be a good place to start, after all, who doesn’t love the South Pacific – the tropical climate, abundant fresh fruit and diverse reef diving possibilities? Heidi imagines her eyebrows sipping mojitos on the beach at sunset, reclining comfortably in a palette of fuchsia, orange and red. Heidi feels buoyed by this new possibility.

The eyebrows dive in and grace a lovely brown woman named Lulu. Lulu is holding a basket of fruit, talking to her friend; their strong, sexually ambiguous bodies are adorned with pearls and flowers, rendering them at once feminine and ambivalent, as if Gaugin believed the virtues of women were equal to the virtues of men. Indeed, the whole transition goes well, at first, but then Terence returns from a FIFO visit to the PNG mine, tired as hell, officially scheduled for a week off but can’t stay away. His mobile buzzes:

‘They did fucking what?

The eyebrows sit up.

‘Well cut the chains God dammit. Every minute the PNG mine’s closed costs us $4 million!’

Pause.

‘Na, no. No way. We’re not negotiating shit. Without Adonis Mines they’d still be up the river living as savages.’

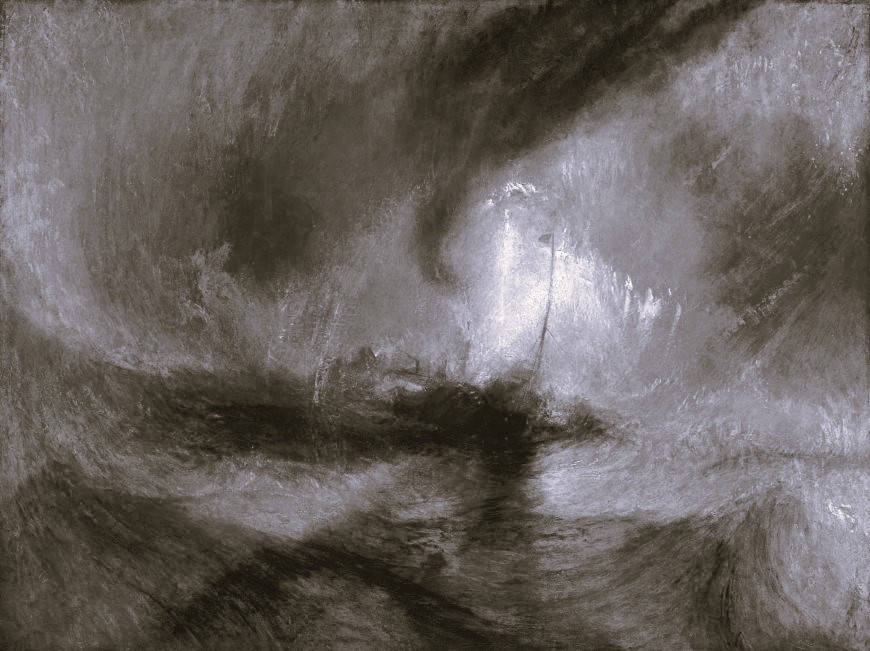

The lovely brown Gaugin ladies and men put down their baskets and look up. Rain spatters the floor-to-ceiling windows as a summer storm begins to close in.

‘No. I never committed to procuring 600 meals a day from those fuckers. It must have been Leila in CSR … do-gooding, social licence bullshit.’

The rain sets in heavier now. It pounds at the windows causing Terence to yell more loudly still into the void of his phone.

‘Well yeah, of course the wastewater’s toxic. It’s a fucking goldmine. Haven’t you ever looked South – used to be rainforest … shit grows there now.

No. I didn’t tell them to put up greenhouses next to the mine, did you? Their choice … probably thought we’d give them more fucking compensation.’

Lulu would like to know if anyone asked the villagers whether they wanted a mine in the first place. From what she can tell, the villagers have lost their land, their homes and their livelihoods, but thankfully the vaults of gold backing up the world’s currencies are secure.

Wind whips the palms outside. Lulu and her friends hunker down as the tail-end of the Category 4 sinks its teeth in.

‘Offer them some more beads, glue and – hell – My Little Ponies if you have to,’ shouts Terence. ‘Failing that, pack them all into trucks, ship them back to their village and post Darkwind security at every fucking gate.

And tell Bob to fly in the papayas from Darwin, that’s local. Relatively speaking. The hell I’m gonna eat radioactive fucking papayas.’

Terence slams the phone against the wall. He doesn’t care. He has five more phones.

The storm rages all that night, and the next, and the next. Water gushes over the gutters, spills up from the drains, and cascades down the stairs of the riverfront mansion. The Brisbane River rises.

Terence is onto fourth fifth phone now, still yelling. ‘Of course it’s unseasonable … No. Definitely not climate change … we only mine clean coal … Yes, like I said, we have to evacuate! I don’t care. Just. Fucking. Do it!’

As the Brisbane River caresses the steps of Terence’s house, a roar is heard over the thrashing weather. A helicopter descends onto Terence’s rooftop helipad; six men in black camo descend the stairs, grab Terence’s safes; his sculptures; his wife’s diamonds and pearls and deliver them to the helipad. As they come back for the paintings, brown, torrential floodwater surmounts the infinity pool and pushes under the sliding glass doors.

The Gaugins are evacuated, their home inundated by rising water. The eyebrows consider the irony of a mining magnate’s home being subsumed by the very climate-induced extreme weather events his company helped precipitate (no laughing matter though the millions of Pacific Islanders at risk of statelessness. Where will they go? Will they know anyone when they get there? Who knows if they’ll be able to work, to vote. The eyebrows don’t, so they make a dive for it, grab on to a floating pool doughnut and sail down the swollen river back to Heidi’s house.)

Heidi is deeply distressed that the Gaugin option failed. She pops right online to see if she can find something more suitable, less miney, less exposed to the elements. On Airbnb she finds a cute townhouse in leafy Bardon, a stone’s throw from Mt Cootha walks. It has a chef’s kitchen, city views. She imagines the eyebrows decked in their Lornas, chatting and sipping soy lattes on their morning walk up the mountain.

The eyebrows approach their new residence with resilience and open-mindedness. They like their room-mate Mila, a Ukrainian sex worker, displaced by the Russian invasion. From where they sit, everyone has to make a living somehow, and with the rising cost of living, beggars can’t be choosers. They eyebrows don’t know if operating a sex business from the apartment is against Airbnb rules, less do they care.

Unfortunately for Mila, the owner of the apartment finds out about Mila’s entrepreneurial activities and does care. Paula happens to be Terence’s wife, and when she isn’t in the salon, shopping or in rehab, her job is to “manage the portfolio”. The eyebrows are deeply suspicious of Paula, as Paula’s eyebrows don’t move at all: they’re cemented to her face like smashed china in a mosaic. The eyebrows add “botox” to their list of unlikeable Paula characteristics and unenriching Paula hobbies.

Paula wants Mila out immediately. She considers whether installing a covert surveillance system in the apartment to provide the evidence she needs to break Mila’s contract and dislodge her is against Airbnb rules (yes, also state, federal and common law, advises her lawyer). So Paula calls the ATO on Mila. Unfortunately, Mila owes $10,000 in back taxes, the only thing she possesses is the eyebrows, so when Mila is sent a summons by the ATO instructing her to relinquish the eyebrows or risk deportation, the eyebrows hightail it back to Heidi’s. Again.

At this point Heidi is unsure what more she can do for the eyebrows, now looking over her shoulder whilst she researches her next piece on Australia’s immigration crisis. Together they read the case of Ismail Hussain, a refugee who was imprisoned in Melbourne’s Park Hotel, behind tinted windows that couldn’t open to let in the fresh air and sunlight. Pale and broken, he took sleeping pills day and night to make the time pass more quickly. For two years. Heidi’s stomach churns with an incendiary mix of anger and sorrow.

A measure of a society is how it welcomes strangers, thinks Heidi. The eyebrows nod, knowingly.

When do we open the door, and when do we keep it firmly shut? This has been the question all along, the eyebrows think.

Heidi realises that the eyebrows are a mirror for the best and worst in her – her best critic – and this has been their purpose all along.

‘Hospitality has a paradox at its heart,’ thinks Heidi. ‘On the one hand, rights and duties are imposed on the women and men who give a welcome, as well as on the women and men who receive it. On the other hand, for hospitality to fulfil its promise, to be absolute, it would need to transgress the very laws in which it’s been inscribed.’

Heidi imagines a new home for the eyebrows, a home in which people say ‘yes’ to whomever or whatever shows up, regardless of their name, race, or species, whether they are human, animal or divine. Where there are no rules. Where hospitality is unconditional.

She opens her computer and begins to type:

Relieved of her eyebrows, Heidi feels a renewed sense of purpose, a development so affronting from the eyebrows’ perspective they feel compelled to leave Heidi a note.

Heidi welcomes the eyebrows into the home of her story, where they live, happily ever after.

Ali Buchberger

Ali Buchberger is a Brisbane-based writer, former concert pianist, diplomat in Africa and CEO of a robotics company. She is a regular contributor to trade and mainstream media publications, including Space Connect, Australian Space Outlook and the ABC, and was recently long listed for the Marj Wilkie Short Story prize. She is a graduate of University of Cambridge.

![]()

Back to Issue

Also in this thread

This thread has no other posts